Embark on a journey to elevate your running with How to Analyze Your Running Form for Better Efficiency. This guide provides a comprehensive exploration of running mechanics, offering insights into optimizing your technique for enhanced performance and reduced injury risk. We’ll delve into the core principles that underpin efficient running, providing you with the knowledge and tools to assess and refine your form.

Discover the secrets to unlocking your running potential. From understanding the biomechanics of each stride to leveraging technology for data-driven insights, this resource equips you with practical strategies. Learn how to identify common form errors, implement corrective exercises, and track your progress towards becoming a more efficient and resilient runner. Whether you’re a beginner or a seasoned marathoner, this guide offers valuable information to help you run stronger and smarter.

Understanding Running Mechanics

Understanding running mechanics is fundamental to improving running efficiency and reducing the risk of injury. By analyzing the biomechanics of your stride, you can identify areas for improvement and optimize your form for better performance. This involves understanding the key elements that contribute to an effective and economical running style.

Fundamental Biomechanics of Running

Running involves a complex interplay of forces and movements. Several key elements significantly influence running efficiency.

- Stride Length: This is the distance covered with each step. Longer strides, when controlled and efficient, can increase speed. However, excessively long strides can lead to overstriding, increasing ground contact time and the risk of injury.

- Cadence: Cadence refers to the number of steps taken per minute (SPM). A higher cadence is often associated with reduced ground contact time and improved running economy. Many elite runners maintain a cadence close to or above 180 SPM.

- Ground Contact Time: This is the duration your foot is in contact with the ground during each stride. Shorter ground contact times are generally desirable as they minimize the braking effect and allow for more efficient energy transfer.

Phases of a Running Stride

The running stride can be broken down into distinct phases, each characterized by specific movements and joint angles.

- Initial Contact: This is the moment your foot first strikes the ground. Ideally, contact should occur beneath the hips, minimizing the braking force. The ankle is in a dorsiflexed position.

- Midstance: As the body moves over the stance leg, the knee bends to absorb impact, and the ankle plantarflexes. This phase is crucial for shock absorption and preparing for propulsion.

- Propulsion: The body drives forward, and the ankle plantarflexes powerfully as the foot pushes off the ground. The hip extends, and the knee straightens.

- Swing Phase: The leg swings forward, preparing for the next ground contact. The knee flexes, bringing the heel towards the glutes, and the hip flexes.

Joint Angles During the Running Cycle

Joint angles play a critical role in running efficiency. Optimal ranges help ensure efficient force transfer and minimize the risk of injury.

- Knee Angle: During initial contact, the knee should be slightly flexed (around 15-20 degrees) to absorb impact. During midstance, the knee flexes further (around 40-50 degrees). In the propulsion phase, the knee extends as the leg pushes off.

- Hip Angle: The hip extends during the propulsion phase, generating forward momentum. The range of motion at the hip should be adequate for a powerful push-off.

- Ankle Angle: At initial contact, the ankle is dorsiflexed. During midstance, the ankle plantarflexes to absorb impact. During propulsion, the ankle plantarflexes powerfully, providing the final push-off.

Observing Your Form

Analyzing your running form visually is a powerful way to identify areas for improvement. By understanding how your body moves, you can make adjustments to run more efficiently and reduce your risk of injury. This section will guide you through the process of self-assessment using video and highlight key visual cues to focus on.

Performing a Self-Assessment Using Video Recording

Recording yourself running provides invaluable insights into your form. It allows you to observe movements that are difficult to perceive while running. The following steps will help you set up your video recording effectively.

- Choose Your Location: Select a flat, even surface like a track or a smooth road. Ensure there is adequate space for you to run a comfortable distance. Consider running near a landmark or a spot you can easily identify to compare the performance.

- Camera Placement: Camera placement is crucial for capturing the right angles.

- Front View: Position the camera directly in front of you at a distance that allows you to capture your entire body. The camera should be at approximately hip level. This angle is helpful for observing leg alignment, foot strike, and arm swing.

- Side View: Place the camera perpendicular to your running path. The camera should be positioned at hip level. This angle allows you to analyze your posture, knee lift, and foot strike in more detail.

- Rear View: Position the camera behind you, again at hip level. This angle helps assess arm swing and overall body alignment.

- Recording Distance: Record yourself running for at least 20-30 seconds at a comfortable, sustainable pace. This allows you to capture multiple strides and identify any consistent patterns in your form.

- Lighting: Ensure adequate lighting to provide a clear view of your movements. Avoid recording in direct sunlight, which can cause harsh shadows.

- Repeat and Vary: Record yourself at different paces and on different surfaces to identify how your form changes.

Specific Visual Cues to Look For When Analyzing Running Form

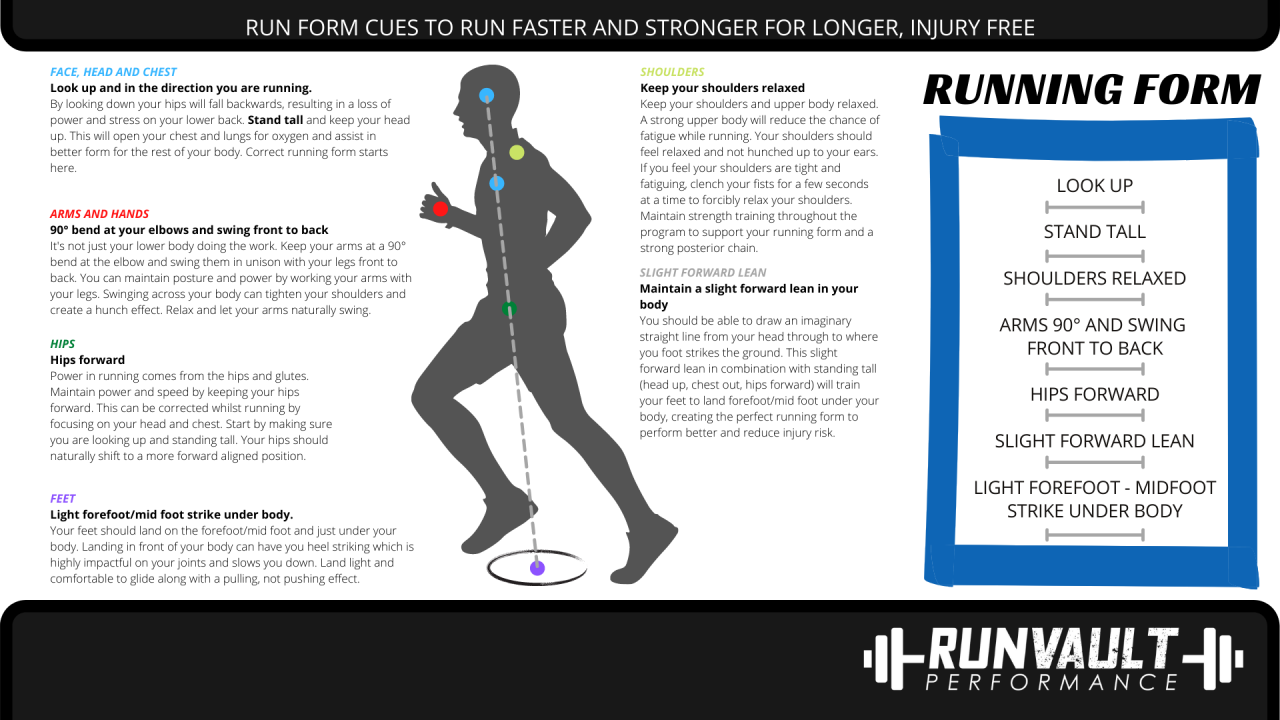

When reviewing your video, focus on these key areas to assess your running form.

- Arm Swing: Observe the movement of your arms. Your arms should swing forward and back, not across your body. Your elbows should be bent at approximately 90 degrees.

- Foot Strike: Analyze how your foot lands. Ideally, you should aim for a midfoot strike, where the middle of your foot makes contact with the ground first. Avoid overstriding, where your foot lands far in front of your body.

- Posture: Maintain an upright posture with a slight lean from the ankles. Avoid slouching or leaning too far forward or backward. Keep your head up and your gaze forward.

- Knee Lift: Observe the height of your knee lift. A good knee lift contributes to stride length and efficiency.

- Cadence: Count the number of steps you take per minute (SPM). A higher cadence, generally above 170 SPM, is often associated with improved efficiency and reduced injury risk.

Common Form Errors and Corrections

Identifying form errors is the first step toward improvement. The following table Artikels common running form errors, their impact, and suggested corrections.

| Error | Description | Impact | Correction |

|---|---|---|---|

| Overstriding | Landing with your foot far in front of your body. | Increased braking force, increased stress on knees and hips, reduced efficiency. | Focus on landing beneath your hips. Increase your cadence. Visualize landing your foot under your center of gravity. |

| Excessive Vertical Oscillation | Bouncing up and down excessively while running. | Wasted energy, increased impact forces. | Focus on maintaining a stable head position. Think about running “smoothly” rather than “bouncing.” |

| Cross-Body Arm Swing | Swinging your arms across your body. | Inefficient use of energy, potential for shoulder strain. | Focus on swinging your arms forward and back, keeping them close to your body. Imagine your arms moving in a straight line. |

| Slouching | Rounding your shoulders and hunching your back. | Reduced lung capacity, inefficient breathing, increased stress on the spine. | Maintain an upright posture with your shoulders relaxed. Engage your core muscles. Imagine a string pulling you up from the top of your head. |

| Heel Striking | Landing on your heel first. | Increased impact forces, increased risk of injury, inefficient use of energy. | Focus on landing with a midfoot strike. Imagine “grabbing” the ground with your foot. |

Assessing Foot Strike and Its Impact

Understanding your foot strike is crucial for running efficiency and injury prevention. The way your foot hits the ground has a significant impact on how your body absorbs shock, how efficiently you use energy, and your overall risk of injury. This section will delve into the different foot strike patterns, their advantages and disadvantages, and how footwear influences your running form.

Foot Strike Patterns: Forefoot, Midfoot, and Heel

There are three primary ways a runner’s foot can strike the ground: forefoot, midfoot, and heel strike. Each has distinct characteristics.

- Forefoot Strike: In a forefoot strike, the ball of the foot and toes make initial contact with the ground. This is often associated with a higher cadence (steps per minute) and shorter stride length.

- Midfoot Strike: The midfoot strike involves the middle part of the foot landing first. This pattern often distributes the impact more evenly across the foot.

- Heel Strike: Heel striking is characterized by the heel making initial contact with the ground. This is the most common foot strike pattern among recreational runners.

Comparative Analysis of Foot Strike Patterns

The choice of foot strike pattern impacts both energy expenditure and injury risk. Understanding these trade-offs can help you optimize your running form.

- Energy Expenditure:

Forefoot striking often requires more energy initially because of the increased ankle muscle activation. However, it can lead to more efficient energy return, especially at higher speeds. Midfoot striking may offer a more balanced approach, potentially reducing overall energy expenditure compared to heel striking. Heel striking can be less efficient, as it often leads to a braking effect, wasting energy.

- Injury Risk:

Heel striking can increase the risk of impact-related injuries like stress fractures and knee problems due to the greater impact forces concentrated on the heel. Forefoot striking may reduce this risk, but it can increase the strain on the calf muscles and Achilles tendon. Midfoot striking often distributes the impact more evenly, potentially reducing the risk of certain injuries.

However, the best foot strike pattern is individual and dependent on factors like running speed, terrain, and overall biomechanics.

Impact of Footwear on Foot Strike and Running Efficiency

Footwear plays a crucial role in influencing foot strike and overall running efficiency. The design of a running shoe can either encourage or discourage certain foot strike patterns.

- Shoe Cushioning: Highly cushioned shoes can encourage heel striking because the cushioning absorbs the initial impact. Minimalist shoes, on the other hand, often promote midfoot or forefoot striking.

- Heel-to-Toe Drop: The heel-to-toe drop (the difference in height between the heel and the forefoot) influences foot strike. Shoes with a high heel-to-toe drop (e.g., 10-12mm) often encourage heel striking, while shoes with a lower drop (e.g., 0-4mm) may facilitate a midfoot or forefoot strike.

- Shoe Flexibility: More flexible shoes can allow for a more natural foot motion, potentially encouraging a midfoot or forefoot strike. Stiffer shoes may limit this natural movement and promote heel striking.

- Example: Consider a study published in the

-Journal of Sports Sciences* that compared running economy in runners wearing traditional running shoes versus minimalist shoes. The study found that runners in minimalist shoes showed a slight improvement in running economy and a tendency towards a more midfoot strike pattern, compared to those in traditional running shoes. (Reference:

-Journal of Sports Sciences*, date and authors should be included).

Evaluating Cadence and Stride Length

Understanding cadence and stride length is crucial for optimizing running efficiency. These two factors are intrinsically linked and play a significant role in how efficiently you use energy while running. Analyzing them allows you to identify areas for improvement and potentially reduce your risk of injury.

Calculating Cadence and Stride Length

Cadence refers to the number of steps you take per minute (SPM), and stride length is the distance covered with each step. Calculating these metrics is straightforward.To determine your cadence:

- Count the number of times your foot (either foot) strikes the ground in one minute while running at a comfortable pace.

- Alternatively, count the number of times your foot (either foot) strikes the ground for 30 seconds and multiply by two.

To determine your stride length:

- Measure the distance you cover in a certain number of steps. For example, measure the distance covered in 10 steps.

- Divide the total distance by the number of steps to find the average stride length.

- Alternatively, use a running watch with GPS to measure your stride length.

The relationship between cadence, stride length, and running speed is represented by the following formula:

Speed = Cadence x Stride Length

Increasing your speed involves either increasing your cadence, increasing your stride length, or a combination of both. However, focusing on cadence is often recommended for improved running economy and injury prevention.

Impact of Cadence and Stride Length on Running Economy

Both cadence and stride length directly affect running economy, which is the amount of oxygen (and energy) you use to run at a given speed.* Cadence: A higher cadence generally leads to better running economy. A faster cadence often reduces the vertical oscillation (bouncing) and the braking forces experienced with each foot strike. This reduces the energy wasted on non-propulsive movements.

A common recommendation is to aim for a cadence of at least 170-180 SPM.

Stride Length

Stride length affects running economy, but not always in a linear way. While a longer stride length can increase speed, it can also lead to overstriding, where the foot lands too far in front of the body. Overstriding can increase impact forces and reduce running economy.

Optimizing Cadence and Stride Length

Optimizing these metrics involves finding the ideal balance for your individual characteristics. Several factors, including your height, leg length, and running experience, influence your optimal cadence and stride length.* Individual Runner Characteristics: Taller runners tend to have a naturally longer stride length than shorter runners. However, they may still benefit from increasing their cadence. Runners with more experience and better running form often demonstrate a more efficient cadence and stride length.

General Guidelines

As mentioned, aiming for a cadence of 170-180 SPM is a good starting point. Experiment with small increases in cadence while maintaining your speed to find your optimal range. Gradually increasing cadence can help you avoid overstriding and improve running economy.

Drills to Improve Cadence and Stride Length

Incorporating drills into your training can help improve both cadence and stride length. These drills should be performed regularly as part of your warm-up or during specific training sessions.

- High Knees: This drill emphasizes lifting your knees high with each step, promoting a quicker leg turnover and improved cadence.

- Butt Kicks: This drill focuses on bringing your heels up towards your glutes, which helps to increase leg turnover and promotes a faster cadence.

- A Skips: This drill involves skipping with a high knee lift and a focus on driving the arms. It helps to improve coordination and leg turnover.

- Fast Feet: This drill involves running in place as quickly as possible, focusing on a high cadence and quick foot turnover.

- Stride Outs: These are short bursts of faster running (e.g., 50-100 meters) where you focus on maintaining good form and increasing your speed, which can improve stride length and efficiency.

Analyzing Posture and Upper Body Mechanics

Maintaining good posture and utilizing proper upper body mechanics are crucial for efficient running. They contribute significantly to your overall running economy, reducing wasted energy and minimizing the risk of injuries. A well-aligned posture allows for optimal oxygen intake and efficient force transmission, while coordinated arm movements provide balance and propulsion. Neglecting these aspects can lead to fatigue, decreased performance, and potentially, long-term musculoskeletal issues.

Upright Posture and Its Effect on Running Efficiency

An upright posture is fundamental to efficient running. It’s not about being rigidly stiff, but rather maintaining a tall, relaxed carriage. This alignment optimizes the biomechanics of your stride, allowing for a more direct transfer of energy and reducing unnecessary strain on your joints.

- Benefits of Upright Posture: An upright posture facilitates better breathing by opening up the chest cavity, allowing for deeper breaths and increased oxygen intake. It also helps to reduce the impact forces on your joints, as your body weight is more evenly distributed. This leads to improved running economy, meaning you can run faster with less effort.

- Consequences of Poor Posture: Slouching or leaning forward can restrict your breathing and increase the load on your lower back and hips. This can lead to fatigue, pain, and ultimately, a less efficient running stride. For instance, a study published in the

-Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research* found that runners with poor posture exhibited a significantly higher rate of oxygen consumption, indicating a less efficient running style. - Achieving Upright Posture: Imagine a string pulling you up from the crown of your head. Relax your shoulders and keep your core engaged. Your gaze should be focused slightly ahead, not down at your feet. Regular core strengthening exercises, such as planks and bridges, can help improve your posture and core stability.

Arm Swing’s Contribution to Propulsion and Balance

The arm swing is not merely a cosmetic element; it plays a vital role in propelling you forward and maintaining balance. Proper arm movement helps to counteract the rotational forces generated by your legs, preventing excessive side-to-side motion and conserving energy. The rhythm of your arm swing should ideally synchronize with your leg turnover, contributing to a smooth and efficient stride.

- Arm Swing’s Role in Propulsion: The arm swing acts as a counterbalance, generating momentum that contributes to forward motion. The forward swing of the arms assists in driving the legs forward, increasing stride length and overall speed.

- Arm Swing’s Role in Balance: As your legs move forward, your arms swing in opposition, preventing excessive rotation of your torso. This helps to maintain a stable center of gravity, minimizing wasted energy and reducing the risk of injury.

- Optimizing Arm Swing: The arms should swing forward and backward, not across the body. Keep your elbows bent at approximately 90 degrees, and your hands relaxed. Avoid clenching your fists, as this can lead to tension in your shoulders and neck.

Correct and Incorrect Arm Swing Techniques

Understanding the nuances of arm swing is crucial. Comparing the correct and incorrect techniques can help you identify areas for improvement in your own running form.

| Feature | Correct Arm Swing | Incorrect Arm Swing |

|---|---|---|

| Arm Angle | Elbows bent at approximately 90 degrees. | Elbows too straight or too bent (less than 70 or more than 110 degrees). |

| Hand Position | Hands relaxed, near the waist level, swinging forward and back. | Clenched fists, hands crossing the midline of the body, or swinging too high or low. |

| Shoulder Position | Shoulders relaxed and down, not tense or hunched. | Shoulders tense, hunched up towards the ears. |

| Motion | Arms swing forward and back, close to the body. | Arms swinging across the body, leading to excessive torso rotation. |

| Description | Imagine a pendulum swinging directly forward and back from the shoulder. The hands stay relatively close to the body. The motion is relaxed and controlled. The elbow angle remains consistent. | The arms swing across the body, like windshield wipers, causing the torso to rotate excessively. The hands may cross the midline. The elbows may be locked out or bent at an extreme angle. The shoulders are often tense and elevated. |

Using Technology to Gather Data

Wearable technology has revolutionized how runners analyze their form, offering a wealth of data previously inaccessible to the average athlete. GPS watches, foot pods, and even specialized insoles provide objective measurements that can help identify inefficiencies and guide training adjustments. This data-driven approach complements visual observation, creating a more comprehensive understanding of your running mechanics.

Data Points Tracked by Wearable Technology

Wearable devices track a variety of metrics, providing insights into different aspects of your running form. Understanding these data points is crucial for effective analysis and improvement.

- Vertical Oscillation: This measures the amount your body moves up and down with each stride, typically expressed in centimeters. Lower vertical oscillation is generally associated with greater running efficiency, as less energy is wasted on upward movement.

- Ground Contact Time: This indicates the duration your foot is in contact with the ground, usually measured in milliseconds. Shorter ground contact time often correlates with improved running economy and efficiency, as it minimizes braking forces.

- Cadence: This is the number of steps you take per minute (SPM). A higher cadence, generally, reduces the impact load on your joints and can improve running efficiency.

- Stride Length: This measures the distance covered with each stride. Stride length and cadence are closely related.

- Heart Rate: This provides insights into your body’s physiological response to running, indicating effort levels and potential fatigue. It can be a useful metric to see if changes to your form are also improving your running economy.

- Balance: Some devices can measure the balance between your left and right legs. Imbalances can lead to inefficiencies and increase the risk of injury.

Interpreting Data from Wearable Devices

Analyzing the data from your wearable device requires understanding the significance of each metric and how it relates to your running form. Comparing your data over time allows you to track progress and identify areas needing attention.

- Vertical Oscillation Analysis:

- If your vertical oscillation is high, consider focusing on drills that promote a more forward, rather than upward, motion.

- Strength training, particularly exercises that strengthen the core and glutes, can also help reduce vertical oscillation.

- Ground Contact Time Analysis:

- If your ground contact time is long, focus on improving your cadence.

- Consider strengthening exercises to improve the stiffness of your lower leg and foot.

- Cadence Analysis:

- Increasing your cadence can reduce impact forces and improve efficiency.

- Aim to gradually increase your cadence by a few steps per minute, using a metronome to guide you.

- Stride Length Analysis:

- While a longer stride length can contribute to faster speeds, excessively long strides can increase ground contact time and vertical oscillation.

- Monitor your stride length in conjunction with cadence to find the optimal balance for your running style.

- Heart Rate Analysis:

- If your heart rate is consistently higher than expected for a given pace, it could indicate inefficient running form.

- Evaluate your form to identify and address any potential issues.

- Balance Analysis:

- If there is a significant difference in balance between your legs, work on strengthening the weaker side.

- Consider consulting with a physical therapist to identify any underlying imbalances.

Remember that the ideal values for these metrics vary depending on individual factors such as height, weight, and running experience.

Implementing Form Corrections: A Step-by-Step Guide

Correcting your running form is a journey, not a destination. It requires patience, consistency, and a structured approach. Trying to overhaul your form overnight can lead to injury and frustration. This guide provides a systematic plan to integrate form corrections into your training, ensuring sustainable improvements and a more efficient running style.

Setting Realistic Goals for Form Improvement

The key to successful form correction is to set achievable goals. Trying to fix everything at once is overwhelming and counterproductive. Instead, focus on one or two key areas at a time.

- Prioritize Based on Impact: Identify the form flaws that have the greatest impact on your efficiency and risk of injury. For instance, overstriding often leads to a higher injury risk, making it a priority.

- Break Down Goals: Instead of aiming for a perfect form immediately, break down larger goals into smaller, manageable steps. For example, if your goal is to reduce overstriding, start by aiming to decrease your stride length by a specific percentage.

- Set SMART Goals: Use the SMART framework to ensure your goals are effective.

- Specific: Clearly define what you want to achieve (e.g., “Increase cadence by 5%”).

- Measurable: Establish how you will track your progress (e.g., “Record cadence during runs”).

- Achievable: Set realistic targets based on your current form and fitness level (e.g., don’t try to increase your cadence by 20% in a week).

- Relevant: Ensure the goals align with your overall running objectives (e.g., improving your marathon time).

- Time-bound: Set a timeframe for achieving your goals (e.g., “Increase cadence by 5% within the next 4 weeks”).

- Track Progress: Regularly monitor your progress using data from your observations and technology. This will help you stay motivated and make necessary adjustments to your plan.

Exercises and Drills to Address Common Form Flaws

Targeted exercises and drills can help address specific form issues. These exercises, when performed consistently, can retrain your body to move more efficiently.

- Overstriding: Overstriding occurs when your foot lands significantly in front of your center of mass. This increases impact forces and reduces efficiency.

- High Knees: This drill emphasizes bringing your knees up high, promoting a midfoot strike. Perform this drill for 30-60 seconds. Focus on maintaining a quick turnover.

- A-Skips: A-Skips involve a skip with a high knee drive and a powerful push-off. This encourages a more upright posture and a quicker cadence. Do this for 30-60 seconds.

- Cadence Drills: Practice running at a higher cadence (steps per minute). Gradually increase your cadence over time, aiming for around 170-180 steps per minute. Use a metronome or a running watch to help you maintain the pace.

- Excessive Vertical Oscillation: Vertical oscillation is the amount your body moves up and down while running. Reducing this can conserve energy.

- Bounding: This drill helps improve your ability to generate power with each stride. Focus on minimizing ground contact time. Perform for 30-60 seconds.

- Plyometric Exercises: Exercises like box jumps and jump squats can increase power and reduce ground contact time. Start with low boxes and gradually increase the height.

- Poor Posture: Slouching or leaning too far forward or backward can reduce efficiency.

- Posture Drills: Practice running with a tall posture, engaging your core, and looking straight ahead. Visualize a string pulling you up from the crown of your head.

- Core Strengthening Exercises: Strong core muscles help maintain proper posture. Include exercises like planks, side planks, and Russian twists in your routine.

- Arm Swing Issues: Inefficient arm swing can negatively affect your overall running form.

- Arm Swing Drills: Practice swinging your arms forward and back, keeping your elbows bent at a 90-degree angle. Avoid crossing your arms across your body.

- Shadow Running: Run in front of a mirror or film yourself to check your arm swing.

Designing a Training Schedule that Incorporates Form Drills

Integrating form drills into your regular training schedule is crucial for reinforcing the changes. Consistency is key to seeing results.

- Warm-up: Always include a dynamic warm-up before each run. This should include exercises like leg swings, arm circles, and torso twists to prepare your body for the workout.

- Form Drill Integration:

- Easy Runs: Incorporate form drills for 5-10 minutes at the beginning or end of your easy runs. This helps reinforce good habits when you’re not fatigued.

- Interval Workouts: Include form drills during the recovery periods between intervals. This helps you maintain good form even when you are tired. For example, after a hard interval, perform high knees for 30 seconds.

- Long Runs: Break up your long runs with short bursts of form drills every 20-30 minutes. This can help prevent form breakdown as fatigue sets in.

- Strength Training: Schedule strength training sessions 1-2 times per week to support your form improvements. Focus on exercises that strengthen your core, glutes, and hamstrings.

- Rest and Recovery: Allow for adequate rest and recovery to prevent injuries. This includes rest days, proper nutrition, and sufficient sleep.

- Example Weekly Schedule:

- Monday: Rest or Cross-training (e.g., swimming, cycling).

- Tuesday: Easy Run (30-45 minutes) + Form Drills (High Knees, A-Skips, Cadence Drills).

- Wednesday: Strength Training.

- Thursday: Interval Workout (e.g., 6 x 400m repeats) + Form Drills (A-Skips during recovery).

- Friday: Rest or Easy Run.

- Saturday: Long Run (60+ minutes) + Form Drills (every 20-30 minutes).

- Sunday: Rest or Cross-training.

- Progressive Overload: Gradually increase the duration and intensity of your form drills over time. For example, increase the time you spend doing drills from 5 minutes to 10 minutes.

- Listen to Your Body: Pay attention to any pain or discomfort. If you experience any issues, stop the drills and consult with a running coach or physical therapist.

Seeking Professional Guidance

Improving your running form can be a journey, and sometimes, the best way to reach your goals is with expert help. While self-assessment is a great starting point, consulting with a running coach or physical therapist can provide valuable insights, personalized feedback, and a tailored plan to optimize your form and prevent injuries. These professionals bring a wealth of knowledge and experience that can accelerate your progress and ensure you’re running as efficiently and safely as possible.

Benefits of Consulting a Running Professional

Working with a running coach or physical therapist offers several advantages that can significantly impact your running performance and well-being. They can help you identify and correct inefficiencies, reduce the risk of injuries, and develop a training plan that aligns with your individual needs and goals.

- Expert Analysis: Professionals have a trained eye for spotting subtle form flaws that you might miss on your own. They can provide objective assessments and offer specific recommendations for improvement.

- Personalized Feedback: A coach or therapist can tailor their advice to your unique running style, biomechanics, and goals. They consider your strengths, weaknesses, and any existing injuries or limitations.

- Injury Prevention: By identifying and addressing form issues, professionals can help you minimize the risk of common running injuries, such as runner’s knee, plantar fasciitis, and stress fractures.

- Performance Enhancement: Improved form leads to greater running efficiency, allowing you to run faster and with less effort. This can result in improved race times and a more enjoyable running experience.

- Structured Training Plan: Coaches can create training plans that incorporate form drills, strength training, and other elements to support your overall running goals.

Questions to Ask a Running Professional

When consulting a running professional, asking the right questions can help you gain a deeper understanding of your form and how to improve it. Prepare a list of questions beforehand to ensure you make the most of your consultation.

- What are my key form strengths and weaknesses? This helps establish a baseline understanding of your current form.

- What specific form corrections do you recommend? Get concrete advice on what to change and how to implement it.

- How can I incorporate these corrections into my training? Understand how to practice and integrate the recommended changes into your running routine.

- What drills or exercises can I do to improve my form? Learn about specific exercises to strengthen muscles and improve technique.

- What is my ideal cadence and stride length? Receive personalized recommendations based on your form and goals.

- How can I prevent common running injuries? Get advice on injury prevention strategies specific to your form and training.

- How often should I schedule follow-up sessions? Determine the appropriate frequency of check-ins to monitor progress and make adjustments.

- What are the signs that I should stop running and seek medical attention? Understand when to prioritize your health and seek medical attention if needed.

Types of Professional Assessments

Running professionals offer various assessment methods to evaluate your form and provide tailored recommendations. Understanding the different types of assessments can help you choose the most appropriate option for your needs.

- Visual Form Analysis: This involves the coach or therapist observing your running form from various angles (front, side, and back) to identify visible flaws. They may use video recording to slow down and analyze your movements. This is often the starting point for a comprehensive assessment.

- Gait Analysis: Gait analysis is a more in-depth assessment that often utilizes technology to analyze your running mechanics. It can include:

- Video Analysis: High-speed cameras capture your running form, allowing for detailed analysis of joint angles, stride length, and ground contact time.

- Force Plate Analysis: Force plates measure the forces exerted on the ground during each foot strike, providing insights into your foot strike pattern, impact forces, and balance. This can help identify asymmetries and areas of potential injury.

- Wearable Sensors: Sensors placed on your body can track your movement patterns, cadence, and other metrics in real-time, providing data-driven feedback on your form.

- Physical Examination: A physical therapist may conduct a physical examination to assess your range of motion, muscle strength, and flexibility. This helps identify any underlying physical limitations that may affect your running form.

- Personalized Training Plan: Based on the assessment results, the professional will develop a tailored training plan that includes form drills, strength training exercises, and a progressive running schedule. The plan considers your individual goals, experience level, and any physical limitations.

Last Word

In summary, How to Analyze Your Running Form for Better Efficiency empowers you to take control of your running journey. By understanding the key elements of running form, from foot strike and cadence to posture and arm swing, you can make informed adjustments that translate to improved performance and reduced risk of injury. Embrace the process of self-assessment, experiment with corrective exercises, and consider seeking professional guidance to achieve your running goals.

Happy running!